So how do we do what we do? Here you will find a series of articles for those of you with an interest in, or are seeking to, understand pain, the process, referral system in general, the best pathways to take and how to get assistance in your “pain journey”.

Blog - Interesting articles on pain

How to Choose the Right Pain Specialist Clinic: Questions to Ask & What to Look For

Lifestyle And Exercise Strategies to Complement Pain Management

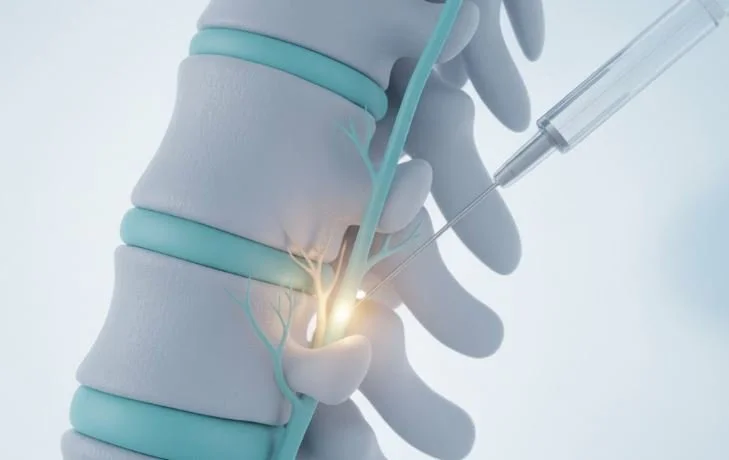

Top 5 Minimally Invasive Interventional Treatments for Back & Sciatica Pain

Understanding Chronic Pain: Why It Persists & What You Can Do

Chronic Pain and Mental Health: How a Holistic approach can help

Post-surgical Pain: Why it occurs and how Specialists treat it

Epidural Steroid Injections vs Nerve Blocks: Key Differences

It all begins with an idea.

What to expect at your first Pain Clinic Appointment in Melbourne

It all begins with an idea.

Neck Pain and Headaches: Causes and when to see a Specialist

It all begins with an idea.

Fibromyalgia Treatment in Melbourne: What Patients Should Know

It all begins with an idea.